The future of leadership: whole system change

“When the best leader’s work is done, the people say ‘We did it ourselves’.”

Lao Tzu

The challenge

In an era of constant disruption, organisations must do two things at once:

- Explore new opportunities and ways of working

- Execute current strategies with discipline

Getting this balance wrong leads to stagnation or chaos. Getting it right demands a new kind of leadership — what we call Ambidextrous Leadership.

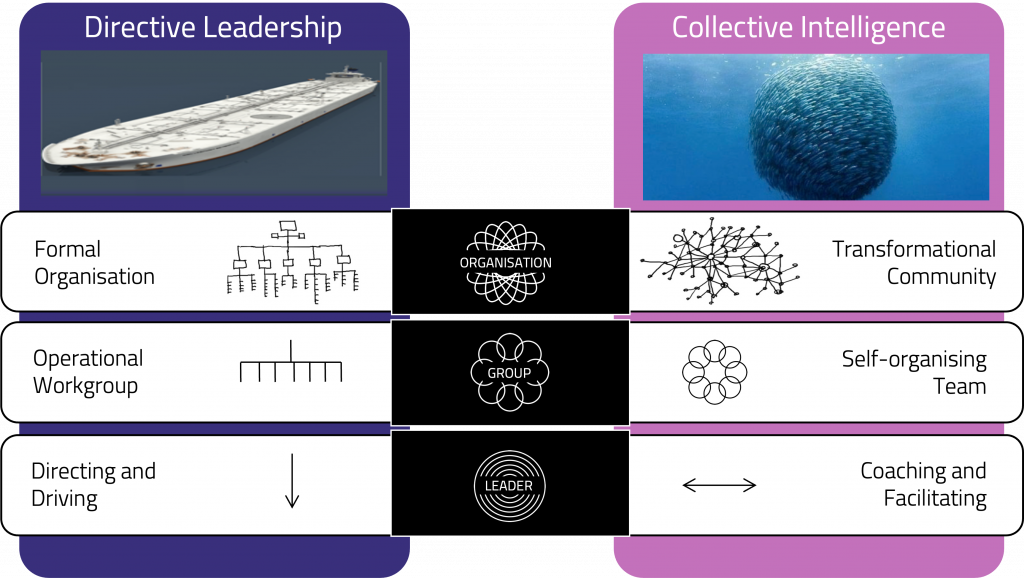

Ambidextrous leaders can move fluidly between Directive Leadership (top-down clarity and control) and Collective Intelligence (whole-system engagement and co-creation).

Why directive leadership alone fails

The directive model — the “organisation as machine” paradigm — served us well in the industrial era. Leaders focused on strategy, structure, and process, optimising each part for efficiency.

But today’s challenges are too complex for command-and-control alone. Markets shift quickly, trust is fragile, and no single leader or function sees the whole picture. Top-down plans often create resistance and miss the relational and creative dimensions of change.

Three kinds of complexity

Disruptive challenges are not just technical puzzles — they are complex, adaptive problems with three distinct layers:

- Systemic complexity: Everyone sees the challenge from where they sit in the system — and no single view is complete. Without synthesis, groups become entrenched in their own perspective and lose sight of the whole. These fragmented views must be surfaced and integrated to create a shared picture of reality.

- Relational complexity: Trust breaks down under pressure, silos form, and collaboration falters. These relational tensions quietly undermine execution — and must be surfaced, repaired, and renewed if the system is to move forward.

- Creative complexity: The future can’t be fully planned — it must be shaped through real-time learning, experimentation, and adaptation. Leaders must create space for collective sense-making and enable the group to co-create solutions as they emerge.

Traditional leadership tools can’t solve these dynamics — they require a different approach.

The power of Collective Intelligence

Collective Intelligence complements Directive Leadership by engaging the whole ecosystem to face challenges together.

1. Addressing Systemic Complexity

Bring together a microcosm of the system — functions, levels, stakeholders — to build “full system sight.” Surfacing diverse perspectives allows the group to see the problem differently and generate breakthrough solutions, not just compromises.

2. Tackling Relational Complexity

Surface and work through the trust gaps and hidden tensions that block progress. When leaders and teams undo the blame loops and projections between groups, they create the conditions for real collaboration.

3. Dealing with Creative Complexity

Run transformation as an iterative process, not a one-off plan. Convene, co-create, test, learn, and reconvene. This develops collective agility, so strategy and execution adapt in real time.

The role of leadership

The job of the leadership team is not to have all the answers but to:

- Set direction and frame the challenge

- Create space for the system to think, feel, and act together

- Guide alignment so local solutions still serve enterprise goals

This takes more time upfront but pays off in ownership, alignment, and lasting transformation.

The payoff

Organisations that integrate Directive Leadership with Collective Intelligence are better able to:

- Break through stuck patterns

- Mobilise cross-boundary collaboration

- Build trust and alignment across the system

- Adapt faster and with less resistance

This is what makes them truly ambidextrous — able to steer with clarity and respond with agility.

In a world where disruption is constant, the organisations that thrive will be those that can think, decide, and act as a connected whole.

Developing Collective Intelligence isn’t a “nice to have” — it’s a strategic capability. And it begins with leaders willing to embrace the paradox of being both hero and host, directing when needed and convening the system when the challenge demands it.

Transformation starts here…

The future belongs to organisations that unlock the power of Collective Intelligence — feeling, thinking, and acting as one. Are you ready to build that capacity? Start the conversation with us.