Ambidextrous leadership

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind and still retain the ability to function.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald

The leadership challenge today

We are living in an age of disruption. The challenges leaders face today don’t come with playbooks — they cut across silos, move fast, and require solutions no one person can see alone.

At Living Systems, we call this the work of ambidextrous leadership: knowing when to take charge and when to unlock the intelligence of the group. In other words, balancing Directive Leadership with Collective Intelligence.

This sounds simple. It isn’t.

The power dilemma

Every leader faces a double bind:

- On one hand, they must provide clarity, direction, and confidence.

- On the other, they must create space for challenge, dissent, and new thinking — even when it means questioning their own assumptions.

This paradox becomes even sharper during disruption. The stakes are high, emotions run hot, and people look to the leader for certainty. The temptation is to default to control — yet that very control can shut down the dialogue that’s needed to solve the problem.

Leaders have to do both: hold authority and invite honesty.

What teams experience

For teams, this shift can be disorienting. On Monday, their leader might be in directive mode — chairing an operational meeting and making fast decisions. On Tuesday, that same leader is asking for unvarnished feedback on strategy, the team dynamic, and even their own leadership.

If psychological safety isn’t strong, this can feel like a trap:

- If I speak up, will there be consequences?

- If I stay silent, am I betraying what I really think?

Too often, teams choose silence. They play the game, avoid the hard truths, and energy drains away. The real issues stay hidden — and progress stalls.

The shift leaders need to make

Breaking this pattern requires more than new tools — it calls for a shift in how leaders think, feel, and act.

At Living Systems, we describe this using the Head, Heart, and Hand of Collective Intelligence:

- Head (Mental Agility): Seeing the system as a whole, questioning assumptions, and reflecting on one’s own thinking.

- Heart (Relational Agility): Building psychological safety, regulating emotion under pressure, and creating trust across difference.

- Hand (Task Agility): Facilitating adaptive action, holding lightly to plans, and letting the group’s insights shape the way forward.

Vertical Development: The Real Work

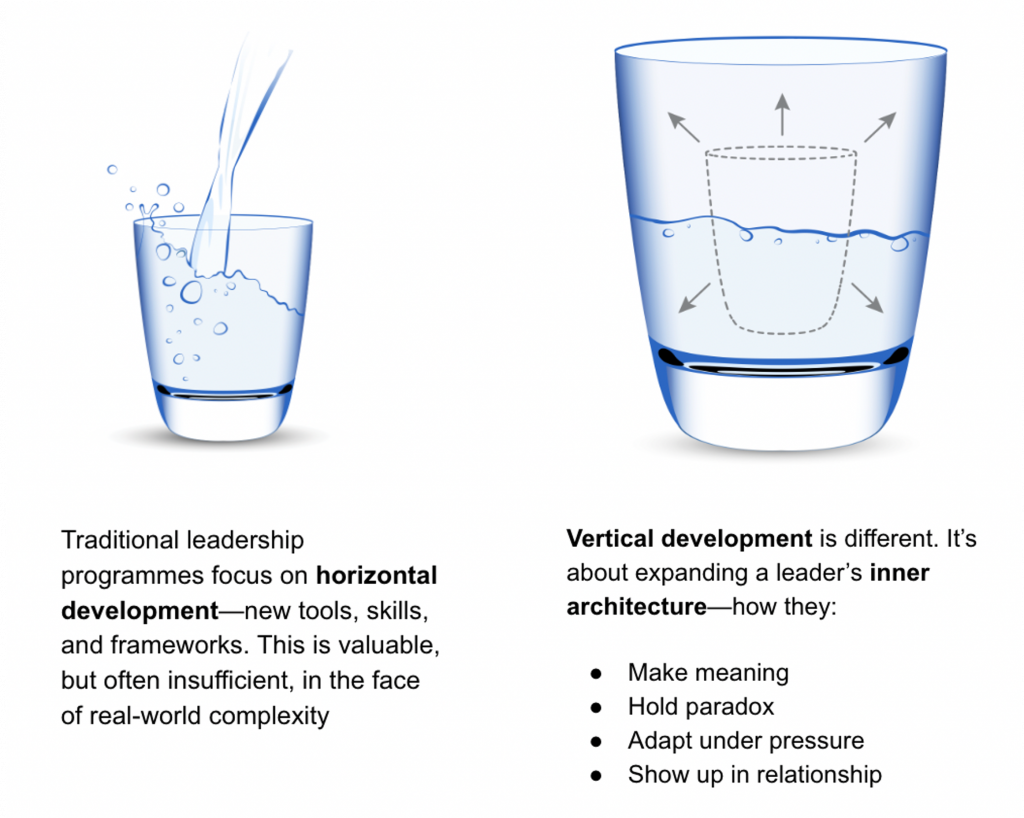

This is not about learning a few new techniques. It’s about vertical development — growing the mental and emotional capacity to operate from a more expansive perspective.

Horizontal development (training, new skills) adds knowledge. Vertical development changes the lens you see the world through. It’s the difference between adding new apps and upgrading your operating system.

Leaders who embrace this journey are better able to:

- Hold paradox without rushing to premature answers

- Stay grounded under pressure

- Invite and integrate challenge without losing authority

A New Kind of Leadership for a New Era

What got us here won’t get us there. The future belongs to leaders who can move fluidly between hero and host — directing when needed, and convening the intelligence of the system when the challenge demands it.

This is leadership that creates trust, unlocks courage, and turns disruption into possibility.

Transformation starts here…

The future belongs to organisations that unlock the power of Collective Intelligence — feeling, thinking, and acting as one. Are you ready to build that capacity? Start the conversation with us.